Fifty Years After Stonewall: A Colorfully Queer Look into the Collection

By Ben French, Curatorial Assistant

In 1969, the patrons of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Lower Manhattan, led a revolt against police forces during a routine raid of their gathering space. The uprising is often cited as a key spark that ignited the formation of the Gay Liberation Movement.

Nine years later, Army veteran Gilbert Baker created the first Pride flag, utilizing the rainbow’s eight distinctive colors to correspond with what he saw as eight empowering forces in LGBTQ life. Contemporary variations of the flag include six of the original rainbow flag colors alongside two stripes to underscore the intersecting communities of Black and Brown LGBTQ-identifying individuals.

In celebration of Pride month and the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, here are eight works from the Columbus Museum’s collection alongside the eight colors of the contemporary Pride flag.

Black: The intersecting lives of Black LGBTQ communities

Jarrett Key, Hair Painting No. 29, 2018, Gouache on canvas

Drawing upon memories of their grandmother telling them of the powerful gift of their (the artist prefers gender-neutral pronouns) hair as a Black individual, Jarrett Key uses their hair not only as a paintbrush but also as a utilitarian and political extension of themselves. Key explores these memories in an ongoing series of “Hair Paintings” that are often made live in performance for an audience of viewers. Watch Key create Hair Painting No. 29 at the Museum here. As marks are made, songs are sung, and fully embodied gestures come forth from improvised dance, Key creates images fraught with formal tension, aesthetic beauty, and political urgency.

Brown: The intersecting lives of Brown LGBTQ communities

Jeffrey Gibson, Upstream, 2016, acrylic on canvas

Jeffrey Gibson’s imagery is as complex as his multicultural upbringing. A gay man born of Choctaw-Cherokee descent, the artist frequently borrows imagery from Native American and pop culture to create paintings, sculptures, and performances pulsating with energy and meaning. Here, Gibson references geometric patterned motifs from Indigenous cultures, 1960s hard-edge paintings, Plains parfleche bags, Pendleton blankets, and environmental concerns. In doing so, Gibson showcases the potentially beautiful creations that can come of intersecting identities and cultures as well as the political complexities inherent in such interactions.

Red: Life

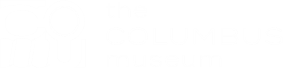

Robert Rauschenberg, Autobiography, 1668, offset lithograph on machine-made, calendared paper

In 1968, Robert Rauschenberg created these three monumental lithographs, which chronicle his life as a queer artist. The first panel depicts an astrological chart of the artist’s birth sign, Libra, laid over a skeleton. In the second panel, a photograph of Rauschenberg’s childhood in Texas grounds a list

of various achievements throughout his lifetime that visually mimic a thumbprint. Finally, the third panel shows the artist in a performance of his first choreographic project, Pelican. Overall, Autobiography stands as a queer artist’s reflection on his own life, complete with its successes and challenges.

Orange: Healing

Best known for her leather-wrapped sculptures of heads, Grossman creates unsettling works exploring ideas of oppression and restriction. The eyes, ears, mouths of her leather-wrapped sculptures are often sewn shut, zippered together, or nailed through. Although not her initial intention, the heads often seem analogous to restrictive gear worn in BDSM cultures. In this light, Grossman creates a dynamic depiction of oppressive power and the potential reclaiming and healing powers hidden in both the animal nature of humanity and the creative process.

Nancy Grossman T.U.F., 1969 Wood, ceramic, leather, metal

Yellow: Sunlight

George W. Dudley Jr ., Yellow House, Seale, Alabama, 1982 Cibachrome print on paper

Within the context of the Pride flag, Sunlight often alludes to ideas of being seen, coming out, making invisible things visible. In 1982, Columbus native George W. Dudley created a series of photographs in Seale, Alabama, in which subjects and objects were painted various colors and put into monochromatic rural scenes. Dudley utilized this same technique in a performance that same year he co-created with Gina Wendkos at MoMA PS1 . Though not much-written record exists of these works, one can see them as creative records of a queer man bringing his invisible imagination and identity to light in campy, assertively ostentatious, public acts of reclaiming rural spaces for queer usage.

Green: Nature

Wes Hempel, The Marriage of History and Fiction, 1996, Oil on canvas

From Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to queer birdwatching together, nature has long stood as a grounds for imagination and freedom in the LGBTQ community. In this work, artist Wes Hempel riffs on a 19th-century work of the same theme but replaces three men with two new figures. In the middle of still a river, a shirtless man presses his hands flat against the “imaginary” picture plane that separates the image from our real life. Using a natural environment as a stage, Hempel’s breaking of the fourth wall invites a playful questioning of notions of difference, reality, and representation.

Blue: Harmony

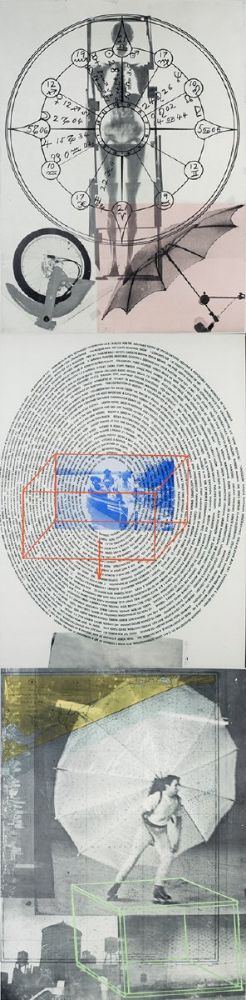

Agnes Martin, Untitled #6 (from the Stedelijk Museum portfolio), 1990, print on vellum

Although Agnes Martin’s work is often exhibited alongside the broad gestural strokes of her fellow New York abstractionists’ paintings, her signature style is much quieter, comprised of meticulous lines on lightly gessoed canvases. After developing this working method in the desert of Taos, New Mexico, Martin moved to New York at the behest of lesbian gallerist Betty Parsons, allowing the tranquility of the East River to influence her work through her use of color. This later work from 1990 highlights the meditative nature of her process that originated from her connection to various spiritualities, from American Transcendentalism to Zen Buddhism.

Purple: Spirit

Mildred Thompson, Untitled (from the Radiation Exploration series), 1994, oil on canvas

Instead of being limited by her age, race, gender, or sexual orientation, Mildred Thompson chose to defy cultural norms by looking to expansive notions of futurism through abstraction. Thompson adopted the visual languages of space exploration, physical science, and music to create works that made invisible processes and experiences visible. In the painting from her “Radiation Exploration” series here, the artist’s vibrant personal and creative energies coexist alongside and within the scientific energy of radiation processes in a flurry of playful brushstrokes and bold colors. By erasing the lines between the personal and the scientific, Thompson created work that held the spirit of what it means to be human in a world of mysterious, chaotic, beautiful phenomena.